How Jean-Luc Godard disappeared from the headlines and into the movies.

By Richard Brody. Published in The New Yorker print edition of the November 20, 2000, issue.

During the 1960 Cannes Film Festival, two months after the release of “Breathless,” his first feature, Jean-Luc Godard told an interviewer, “I have the impression of loving the cinema less than I did a year ago—simply because I have made a film, and the film was well received, and so forth. So I hope that my second film will be received very badly and that this will make me want to make films again.” The twenty-nine-year-old director was not only daring the powers of the movie world to withdraw their approval but begging them to do so: “I prefer to work when there are people against whom I have to struggle.” Godard, who will turn seventy this December, has been struggling ever since; indeed, he could hardly have anticipated the price he would pay for getting his wish.

In the history of cinema, only two other directors have made first full-length films that forever changed the art—D. W. Griffith, with “Birth of a Nation,” in 1915, and Orson Welles, with “Citizen Kane,” in 1941—and they, too, eventually found themselves in exile. Unlike Griffith and Welles, who fought to keep a place in the film industry and then, once excluded, tried to claw their way back in, Godard has remained productive on the margins, but at great personal sacrifice. His single-minded quest to unify his life and his work has had the extraordinary side effect of rendering him out of place in both: hyperreal and disarmingly present in his films; oracular and almost incorporeal in person.

When “Breathless” was first shown, it was an immediate critical and commercial success: no other film had been at once so connected to all that had gone before it and yet so liberating. The plot was a familiar one—a young man gone bad and on the run, the woman he loves unsure whether to run with him—but its execution was utterly new. Shot with a handheld camera in real locations, using available light, and edited with daring visual discontinuity, “Breathless” felt like a high-energy fusion of jazz and philosophy. The actors spoke in hyperbolic aphorisms that leaped from slang to Rilke, and ideas and emotions came and went in a heartbeat; the film resembled a live recording of a person thinking in real time. “Breathless” may not have been as endearing as Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows,” or as intellectually demanding as Alain Resnais’s “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” but in the years to come it inspired New Cinemas from Czechoslovakia to Brazil.

Between 1960 and 1967, Godard made fourteen feature films, including such modernist classics as “Vivre Sa Vie,” “Pierrot le Fou,” and “Two or Three Things I Know About Her,” and in them he continued to outdo both himself and his contemporaries in stretching the limits of narrative film. As a formal innovator, as a social critic, as an unflinching confessor of hot emotions and cold truths, he became a singular figure of the sixties. Writing in Partisan Review in February, 1968, Susan Sontag called him one of “the great culture heroes of our time,” and compared him to Picasso and Schoenberg. During Godard’s 1968 speaking tour of American universities, one student said he was “as irreplaceable, for us, as Bob Dylan.”

Yet by that point Godard was in a crisis of self-doubt; the pace of current events was outstripping his ability to invent new forms to engage them. In the earlier films, he had joyfully embraced the images of mass culture—magazines, advertising, pop tunes, and, above all, Hollywood movies. Now he felt repulsed by the world those images signified and fostered, with its unreflective consumerism and its support for the Vietnam War. The last of this torrent of films, “Weekend”—made famous by a ten-minute tracking shot of a traffic jam (actually three distinct shots, separated by brief intertitles)—concludes with two title cards: the first reads “End of Film,” the second “End of Cinema.” When Godard finished “Weekend,” he advised his production crew to look for work elsewhere. So began Godard’s defiant withdrawal—first from the movie industry, and then from Paris. He did not make another commercial film for more than a decade.

Godard with Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg, filming “Breathless.” Photograph © Raymond Cauchetier // Photograph © Raymond Cauchetier

The films that Godard has made since his return to the movie business, in 1979, are arguably deeper, more technically accomplished, and more daring than the early ones. But they are also far more fragmented in form and rarefied in content, at a time when Hollywood has accustomed even sophisticated viewers to simpler films. This unhappy coincidence, combined with the changed economics of the industry, has made it impossible for any but the most assiduous American fans to keep up with Godard’s work of the past twenty years. The last time a Godard film received a regular commercial release in a first-run theatre in New York was in 1988, when “King Lear” played for three weeks at the Quad Cinema. According to Variety, it took in $61,821 at the box office in all of North America. It is currently unavailable on home video or DVD. The loss is tragic: it’s as if American museums and galleries were to show nothing of Picasso after Cubism.

When I mentioned to some friends that I was going to Switzerland to visit Godard, they were taken aback: they had assumed he was dead. In Godard’s futuristic film “Alphaville” (1965), the hero, Lemmy Caution, Secret Agent 003, is warned that as a romantic individualist he is out of date and doomed. “You will suffer something worse than death,” he is told. “You will become a legend.” This prophecy has been fulfilled in the person of Jean-Luc Godard.

Godard works out of the basement of a modern low-rise residential building in Rolle, the town in Switzerland where he and his partner, Anne-Marie Miéville, have lived since 1978. Godard maintains that the town is outside one of the defining loops of modern life. “Here in Rolle,” he says, “you can’t get a package from Federal Express.”

I asked him why not.

“Because he comes by. I’m never in. He leaves word: ‘Call us.’ So, I don’t call.”

Rolle, set on a hillside by the shores of Lake Geneva, is in timeless harmony with its natural setting. Across the street from the hotel where I was staying was a thirteenth-century castle perched on the banks of the vast, jewel-bright lake. A hundred yards out, a small island with domes of dense foliage pierced by a proud, solemn obelisk resembled a Fragonard come to life; Mont Blanc hovered weightlessly in the distance.

When I arrived at Godard’s office, I could see the filmmaker through a glass door, seated at a broad, uncluttered trestle desk. He was talking on the phone as he waved me in, past one wall of compact disks and another of books and pictures. He sat facing a roomful of video equipment that could stock a small TV station, including a television monitor showing the semifinals of the French Open. (He is an enthusiastic tennis player, and ranks himself “ten-millionth in the world.”)

Godard was wearing black pants, black sandals, and a white T-shirt with a discreet Nike swoosh over the left breast. His hair was sparse and gray, and his face was spiky with white stubble. After several gentle politesses into the phone, he hung up and greeted me. He said that he and Miéville had long admired The New Yorker’s cartoons, and that they had clipped one that exemplified their own situation: a unicorn wearing a suit is seated at a desk and talking on the phone, with a caption reading, “These rumors of my nonexistence are making it very difficult for me to obtain financing.”

I began by asking him about his most recently released feature film, “For Ever Mozart,” from 1996, a bitter fantasy about art and mourning. In it, three young French people with lofty ideas but idle hands take off for Sarajevo to put on a play and are killed in Bosnia by paramilitary thugs. One of the victims is the daughter of an old French director who has been stalled in his work; in his grief, he finds the will to create.

Typically, Godard was not satisfied with the film. “It wasn’t very good,” he said. “The actors aren’t good enough, and things remained too theoretical.” Godard’s complaint about his movie led to a complaint about young actors today: that even unknowns, inundated with media hype, comport themselves like stars and are “less available” to direction: “They think they know what to do, by the fact that they’ve been chosen. They have no doubt. Doubt no longer exists today. With digital, doubt no longer exists.”

This abrupt switch from the sociological to the technological is typical of Godard’s conversation: his sentences, like his films, are always soaring into abstractions, or breaking off, pivoting on an instant of silence to change direction. “With digital, there is no past,” he continued. “I’m reluctant to edit on these new so-called ‘virtual’ machines, these digital things, because, as far as I’m concerned, there’s no past. In other words, if you want to see the previous shot, O.K., you do this”—he tapped the table like a button—“and you see it at once. It doesn’t take any time to get there, the time to unspool in reverse, the time to go backward. You’re there right away. So there’s an entire time that no longer exists, that has been suppressed. And that’s why films are much more mediocre, because time no longer exists.”

Godard is deeply involved with the past, and with the challenges of representing it on film. His new film, “In Praise of Love,” which he is still editing, concerns an elderly French couple in Brittany who are former heroes of the Resistance, and whose life story Steven Spielberg has offered to buy, and the family argument that ensues over whether the offer should be accepted. Spielberg’s presumption to historical authority is one of Godard’s pet peeves. When, in 1995, Godard turned down an invitation to receive an honorary award from the New York Film Critics Circle, he wrote to its chairman declaring himself unworthy of the honor because of his failure to accomplish several things—foremost, “to prevent Mr. Spielberg from reconstructing Auschwitz.”

Spielberg wants “to dominate the world,” Godard charged in 1995, “by the fact of wanting to please before finding truth or knowledge. Spielberg, like many others, wants to convince before he discusses. In that, there is something very totalitarian.” Now, in his office, Godard advanced that argument with an allusion to “Saving Private Ryan,” connecting the Normandy invasion to the invasion by American cinema. “To my mind, I think that’s even the reason why the Americans landed, it’s for the American film, and now it’s happened.” After all, he continued, “when Nixon signed a contract with China, the first thing is always the films. Cheese, airplanes—that comes later.”

Like many contemporary French thinkers, Godard believes that France is enduring an American cultural occupation as significant as the German occupation during the Second World War, and equally hard to resist. He told me about a film he had been close to making that fell through, called “Conversations with Dmitri.” It was about the French film industry under a hypothetical Soviet occupation, and he intended it to be a comment on “the American cultural occupation, the German occupation, all occupations.”

Godard lays much of the blame for what he perceives as the loss of the past, the failure of cultural memory, on the present-day American occupation. He complained to me that the young, media-savvy actors in “For Ever Mozart” didn’t recognize actors from twenty years ago, and suggested, as a corrective, that television should show “only the past, nothing of the present, not even the weather.” He continued, “They should give the weather from twenty years ago. Tennis matches from twenty years ago, not today. But what’s happening today, well, our children will see in twenty years. There’s no hurry—twenty years.”

On the subject of his own past, Godard has relatively little to say, and he has reproached interviewers for dwelling on it. As a child, he was something of a loner, yet he was anything but alone; in fact, he had the kind of refined, close-knit family that one can spend a lifetime trying to escape. Born in Paris, on December 3, 1930, the second of four children, Jean-Luc Godard had a privileged and sheltered childhood. His father, Paul-Jean Godard, was a French-born doctor who became a Swiss citizen; his mother, born Odile Monod, was the daughter of extremely wealthy French bankers. Both were Protestant, and both were literary. Godard credits his father for his taste for German Romanticism and his mother for his love of novels. He spent his childhood reading, skiing, and travelling among his family’s various estates, on both the French and Swiss sides of Lake Geneva. When the Second World War began, Godard was in school in Paris, but he was soon sent back to his family in Switzerland, and he stayed there until the end of the war.

After the Liberation, Godard returned to school in Paris, and in the late nineteen-forties he discovered the Cinémathèque Française. Founded by the young silent-film buff Henri Langlois in 1935, the Cinémathèque included both a collection of films that Langlois had rescued and preserved (at a time when old films were routinely destroyed) and a small screening room where he could show them. It was not the first film museum, but it was the best: Langlois’s catholic taste (which ranged from surrealist fantasies to B Westerns) made the Cinémathèque the hub of postwar French movie culture. There Godard and two other faithfuls of the front row—François Truffaut and Jacques Rivette—eventually introduced themselves. The three young devotees soon met two others, a pharmacy student named Claude Chabrol and a man ten years their senior, Maurice Scherer, now known as Eric Rohmer. Godard’s interest in film quickly grew into an obsession, fuelled by enthusiastic all-night discussions with his new friends while wandering the streets of Paris. To placate his parents, he enrolled at the Sorbonne as a student in ethnology, but he spent all his time at the movies—sometimes watching three films a day, sometimes watching one film (Orson Welles’s “Macbeth,” for example) three times in a row, and sometimes, according to Truffaut, watching “fifteen minutes of five different films in one afternoon.”

At the same time, Godard was doing his best to keep up with his reading: Truffaut reported that his friend would go to people’s apartments and read the first and last pages of forty books. Indeed, Godard had originally wanted to be a novelist, but he felt “crushed by the spectre of the great writers.” Then he discovered “other poets,” in the cinema: “I saw a film of Jean Vigo, a film of Renoir, and then I said to myself, I think that I could do that too, me too.”

During our interview, Godard referred to the New Wave not only as “liberating” but also as “conservative.” On the one hand, he and his friends saw themselves as a resistance movement against “the occupation of the cinema by people who had no business there.” On the other, this movement had been born in a museum, the Cinémathèque: Godard and his peers were steeping themselves in a cinematic tradition—that of silent films—that had disappeared almost everywhere else. Thus, from the beginning, Godard saw the cinema as a lost paradise that had to be reclaimed.

In 1950, Godard published several articles in a short-lived film magazine edited by Rohmer. Then, in 1952, he began to write for a new, intensely serious magazine, co-founded by the legendary film theorist André Bazin: Cahiers du Cinéma. Even his earliest articles displayed the motifs of his future film career: a love for classic American movies, political films, and documentaries; a taste for grandiose speculation and fine phrases; and a conflation of his idea of cinema and his idea of himself. More important, he used his dazzling polymathy to explode the old hierarchies: Hitchcock and Hawks were as great as Eisenstein and Renoir; Eisenstein and Renoir were as great as Voltaire and Cézanne. Godard was already imagining movies that would bring together the commercial cinema, the art cinema, and the whole of Western culture in one madly ambitious body of work—his own.

Godard may have been hatching big plans, but, from his parents’ perspective, he was still living like a spoiled adolescent. In 1952, hoping to thrust responsibility on him, they cut him off financially. Unable to support himself with his film criticism, Godard began stealing—from family members, from friends of the family, from the offices of Cahiers du Cinéma. His mother managed to find him a job with Swiss television, but he stole from his employers and got caught. His father bailed him out of jail and put him in a mental hospital. (These events are strikingly reminiscent of Truffaut’s ordeal in the late nineteen-forties, when he stole a typewriter from his father’s office to finance the creation of his own ciné-club and his father committed him to a psychiatric “observation center.”) After this incident, Godard says, he severed his ties with his family for good.

Shortly afterward, in 1954, Godard went to work on a dam in Switzerland. “I said to myself, ‘I’ll put some money aside, and in two or three years I’ll come back to Paris. I’ll manage to make my first film by age twenty-five.’ That’s the goal that Orson Welles had set.” Instead, he rented a camera on his days off, hired a crew, and made a short documentary about the construction of the dam. He then sold it to the construction company and returned to Paris, where he was able to scrape by on the film’s profits for several years. Eric Rohmer has written of that period, “Whenever people asked us, ‘What do you live on?’ we liked to answer, ‘We don’t live.’ Life was the screen, life was the cinema.”

In Paris, Godard resumed his critical writing for Cahiers du Cinéma and other journals, made several short films, and took a job as the press agent for the Paris office of Twentieth Century Fox. After a screening there of a film by the French producer Georges de Beauregard, Godard told him, “Your film is shit.” This unusual introduction earned Godard an acquaintance that soon proved fruitful: in 1959, following the success of Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows,” Beauregard agreed to produce Godard’s first feature film, on the strength of a story outline written by Truffaut.

From the beginning of his career, Godard crammed more film references into his movies than any of his New Wave comrades. In “Breathless,” his citations include a movie poster showing Humphrey Bogart (whose expression the lead actor Jean-Paul Belmondo tries reverently to imitate); a clip from the soundtrack of the classic film noir “Gun Crazy”; visual quotations from films of Ingmar Bergman, Samuel Fuller, Fritz Lang, and others; and an onscreen dedication to Monogram Pictures, an American B-movie studio. Most of all, the choice of Jean Seberg as the lead actress was an overarching reference to Otto Preminger, who had discovered her for his “Saint Joan,” and then cast her in his acidulous 1958 adaptation of “Bonjour Tristesse.” If, in Rohmer’s words, “life was the cinema,” then a film filled with movie references was supremely autobiographical.

“Breathless” was the first film to make explicit its relation to the history of cinema, and serious critics and viewers appreciated it as such. Yet the wider audience saw it as a gangster movie, and enjoyed the escapist fantasy—a response that took Godard by surprise. In an interview several years after its release, he said, “Now I see where it belongs—along with ‘Alice in Wonderland.’ I thought it was ‘Scarface.’ ” The offhandedly self-righteous thug of “Breathless” was not the scarred sociopath of the real underworld (as he had been in Truffaut’s original conception); he was a character without psychology, a collection of self-consciously cool gestures copied from the movies.

The offhand behavior of Belmondo’s character was mirrored in Godard’s approach to film technique. Like an action painter, he discovered a working method that exalted the inspiration of the moment; in fact, the way the shoot was organized was arguably Godard’s greatest innovation. He had his cameraman, Raoul Coutard, shoot with a handheld camera and scant lighting, partly for aesthetic reasons and partly to save money but mostly to save time. “Three-quarters of directors waste four hours on a shot that requires five minutes of actual directing,” Godard told an interviewer. “I prefer to have five minutes’ work for the crew—and keep the three hours to myself for thought.” He needed time for himself because he made “Breathless” without a storyboard—indeed, without a script. He and his minimal crew usually shot only in the morning, giving the director the rest of the day to come up with what to do next; when he couldn’t come up with anything, they would skip a day of shooting altogether. Jean Seberg, who was used to Hollywood methods, considered quitting after the first day. Two weeks into filming (and not filming), Beauregard thought that Godard was simply wasting money, and threatened to shut down the production, but Truffaut intervened.

In an interview a few years later, Godard was even more explicit about his search for “the definitive by chance”: “As I make low-budget films, I can ask the producer for a five-week schedule, knowing there will be two weeks of actual shooting. ‘Vivre Sa Vie’ took four weeks, but shooting stopped during the whole second week. The big difficulty is that I need people who can be at my disposal the whole time. Sometimes they have to wait a whole day before I can tell them what I want them to do. I have to ask them not to leave the location in case we start shooting again. Of course, they don’t like it.”

In 1960, a young model ignored a telegram from Godard offering her the lead female role in a film he was making. He had noticed her the year before in a soap commercial and had offered her a small part in “Breathless,” which she had refused, because it entailed appearing topless. This time, her friends pushed her to respond. She went to see Godard in his producer’s office, in Paris: “He walked around me three times. He looked me over from head to toe and said, ‘It’s a deal. Come sign your contract tomorrow.’ I asked him, haltingly, what the film was about. He answered that there was no script, that it had to do with politics.” The actress, Anna Karina, was not yet twenty-one, and Godard had to fly her mother in from Denmark to sign on her behalf.

The film, “Le Petit Soldat,” opens with the lines “The time for action is over. I have aged. The time for thought is beginning.” A painfully personal love story set in the context of the French government’s dirty war against Algerian independence fighters and their French sympathizers, the film shows both sides engaging in assassination and torture. As Godard had hoped, it was received badly. The left protested privately; the French government banned the film, blocking its release at home and abroad. “But since I had received death threats in my mailbox,” Godard said, “I was glad it was banned.” Godard, who had called “Breathless” “a documentary on Jean Seberg and on Jean-Paul Belmondo,” here took that notion a step further, asking Anna Karina questions on camera and filming her unscripted answers, a method he expanded and refined in films to come.

Godard and Anna Karina married in 1961. She starred in many of his subsequent films, including “A Woman Is a Woman,” “Vivre Sa Vie,” “Alphaville,” and “Pierrot le Fou,” which used various American movie genres—science fiction, melodrama, romance, the musical—to frame collages of sociology, philosophy, poetry, politics, and outright caprice. The director and his star made a glamorous pair in those years, cruising around Paris in their big Ford, but the marriage was tempestuous. Godard would often disappear; later, Karina would learn that he had been out of the country. As she put it, “He told me, ‘I’m going out for a pack of corn-paper cigarettes,’ and he came back three weeks later.” In 1964, Jacques Rivette, who had just directed Karina in a stage adaptation of Diderot’s “La Religieuse” (which Godard financed), told a journalist, “He and his wife have achieved perfect harmony in destroying each other.” The screenwriter Paul Gégauff described paying a visit to the couple, only to find Godard “stark naked” in a freezing-cold room that had been totally destroyed: “All his clothes and Anna’s were lying on the ground in tatters, the sleeves slashed with a razor, in a mess of wine and broken glass. . . .I noticed Anna on a sort of dais in the far corner of the room, also quite naked. . . .‘I’d offer you a glass of something,’ he said, ‘only there aren’t any glasses left.’ Then: ‘Go and buy us a couple of raincoats so that we can go out.’ ”

Godard thought that Karina was disappointed by the increasingly intellectual path that his film career was taking; he said that “what she really dreamed of was to go to Hollywood.” In “Contempt” (1963), a screenwriter accepts an assignment he despises in order to pay for luxuries that he thinks his beautiful young wife, played by Brigitte Bardot, expects. Michel Piccoli, who played the screenwriter, told a reporter at the time, “I’m not the male lead of ‘Contempt’—he is. He wanted me to wear his tie, his hat, and his shoes.” Raoul Coutard, the film’s cinematographer, said, “I am convinced that he is trying to explain something to his wife in ‘Contempt.’ It’s a sort of letter—one that’s costing Beauregard a million dollars.” (The co-producer Joseph E. Levine concurred: “We lost a million bucks on that lousy film, because that great director Jean-Luc Godard refused to follow the script.”) Years later, Godard said of Karina, “She left me because of my many faults; I left her because I couldn’t talk movies with her.” Karina’s assessment was slightly different: “As soon as we were happy, he tried to get at us by another means, another path. He provoked a new ordeal. One could have thought that it bored him, happiness.” The couple divorced in 1965.

Shortly afterward, Godard made “Masculine Feminine.” Though its twenty-year-old characters—“the children of Marx and Coca-Cola”—were from a different world than the thirty-five-year-old director, the film explores the same conflicts between intellect and desire that fuelled “Contempt.” In “Waiting for Godard,” Michel Vianey’s book about the making of “Masculine Feminine,” Godard told the writer that finding a woman he was attracted to and could talk to would be ideal, “like having the city in the country.”

Godard’s next romantic liaison seemed closer to that ideal, but it precipitated his withdrawal from the film industry, and set the hard terms of his self-exile. Anne Wiazemsky was the granddaughter of the French writer François Mauriac, and the lead actress in Robert Bresson’s “Au Hasard Balthazar.” She and Godard first met after a screening of the rushes, and later, after seeing “Masculine Feminine,” she wrote him a letter. At the time, Wiazemsky was a student at Nanterre University, a nexus of leftist activity. Through his acquaintance with her friends there, Godard conceived “La Chinoise” (1967), a film about a cell of young Parisian Maoists who, from the comfort of a borrowed apartment, plot their first terrorist act. The film, which starred Wiazemsky, is also an unromantic love story, involving her character and another cell member. “La Chinoise” was made a year before the legendary student uprisings, and is widely held to be prescient. That summer, Godard married Wiazemsky, who had just turned twenty; later that year, he made “Weekend.”

When Godard abandoned the movie industry, in 1968, he was fleeing not just a set of narrative conventions, his own public image, and his newfound cinema “family” but also the entrenched customs of movie production. It was no coincidence that the alternative structure he embraced, a doctrinaire Marxism or Maoism, purported to grant workers control of the means of production and to promote collaborative work—in fact, Godard co-founded a Marxist cinema collective the following year. But one scene in “La Chinoise” suggests the inner price of Godard’s doctrinaire ideological allegiance: the hero stands at a blackboard that is covered with the names of famous writers and artists, and erases them one by one, until only the name “Brecht” remains. For a stupendous reader and artistic omnivore like Godard, the scene is the equivalent of intellectual suicide. Describing this period many years later, he told an interviewer, “I didn’t read, I didn’t go to movies, I didn’t listen to music,” and added, citing Rohmer, “ ‘In those years I wasn’t alive.’ ” Ultimately, the reductivism and hortatory optimism of Maoism proved too much. In his semi-apologetic 1972 “Tout Va Bien,” Godard presents Yves Montand as a director who left the cinema in 1968, in a moment of doubt, and has been making TV commercials for a living: Godard was making commercials, but for a political product, and he, too, was looking for a way out. By the time the movie appeared, he and Wiazemsky had separated.

Goddard, left of center, with his first wife, Anna Karina, on the set of “A Woman Is a Woman” (1961); scenes from later films; and from the eight-part video series on the cinema which he completed in 1998. Left: “Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie)” (5); “Hail Mary” / Photofest: Center and text: “Histoire(s) du Cinéma” (Gaumont, 1998). Right: “Passion”; “Prénom Carmen” (3), ©Raymond Cauchetier; “King Lear” / Photofest // Left: “Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie)” (5); “Hail Mary” / Photofest: Center and text: “Histoire(s) du Cinéma” (Gaumont, 1998). Right: “Passion”; “Prénom Carmen” (3), ©Raymond Cauchetier; “King Lear” / Photofest

When I met Michel Vianey in Paris recently, I reminded him of Godard’s quest for a woman he could talk to, and he replied, “Well, he’s found her.” Godard’s thirty-year partnership with Anne-Marie Miéville is a testament to his ongoing attempts to unify filmmaking and domestic life. He first worked with Miéville in 1970, on a film project about Palestinians, and Miéville was closely involved in Godard’s rehabilitation after a severe motorcycle accident the following year. In 1973, the couple left Paris for Grenoble, where they put together their own video studio; there they could control productions from start to finish, and incorporate filmmaking into their daily lives. A few years later, they increased their isolation by moving to Rolle.

Between 1974 and 1978, Godard and Miéville collaborated on three films and two video series, all of which are experimental in the best sense of the word—filled with raw thought and technical innovations—and which served Godard as a laboratory of ideas during the decades that followed. In the late seventies, Miéville coaxed Godard to reconnect with the mainstream film industry in order to make “Every Man for Himself”—but he did it on his own terms. He soon began to refer to “Every Man for Himself,” which was co-written by Miéville, as his “second first film.” Part of the film, at least, was startlingly autobiographical: Jacques Dutronc plays a filmmaker (named Paul Godard) who uneasily follows his girlfriend, also a filmmaker (played by Nathalie Baye), to a new life in the Swiss countryside. As if to confirm the film’s role in reëstablishing him in the cinema, Godard says that “Every Man for Himself” was his only commercial success besides “Breathless.”

With its first shot, a searching view of wispy clouds and vapor trails in a deep-blue sky, “Every Man for Himself” announces one of the principal motifs of Godard’s later films: some of the most sumptuous and awestruck images of nature ever put on film. The presence of nature is simply the presence of Rolle. But the pictorial richness and density can be traced directly to Godard and Miéville’s constant video production in the mid-seventies. Now that Godard had his own studio, he was intimate with his tools and was able to exercise a craftsmanlike virtuosity in every aspect of his art. Starting with this film, Godard, like a painter painting the same apples or model or coastline for twenty years, developed most of his full-length projects from increasingly complex elaborations of a small number of obsessive themes, ranging from the grandly philosophical to the painfully intimate.

Foremost among these themes are the moral combat of filmmaking and the material conditions of the art—sometimes exemplified by an actor playing a filmmaker and sometimes by the saturnine presence of Godard himself. In “Passion” (1982), a filmmaker struggles with the artistic, financial, and emotional complications of a large-scale film, the specifics of which he hasn’t quite figured out; in “First Name: Carmen” (1983), Godard plays Uncle Jean, an involuntarily idled old filmmaker enjoying his dotage in a hospital; in “Soigne Ta Droite” (1987), a director, again played by Godard, is charged with making a film that must be ready for distribution that very night. Having exhausted the stock of mythical Hollywood heroes in the sixties, and of ideological ones in the seventies, Godard was down to his last hero: himself.

After forming his partnership with Miéville, Godard started managing not only his time but also his budget; his involvement in the art of moviemaking became a matter of business. Generally, his budgets are put directly under his control by the producer, and his take is what is left over. This financial arrangement permits him to bring in people and equipment without regard to specific line items, and lets him shoot and reshoot as he chooses. It also challenges him to put up money when necessary. Yet these contingencies, too, he folds back into his art. “What sets me apart from lots of people in the cinema,” Godard has said, “is that money is part of the screenplay, in the story of the film, and that the film is part of money, like mother-child, father-daughter.”

Godard has no children of his own—indeed, he has said that making children and making films are mutually exclusive—but children, real or symbolic, have proved central to his later work. As he has pointed out, “Psychoanalysis and cinema were born in the same year.” In the early eighties, he began to treat the relations of an older director to his young actresses as a variant of the Freudian scenario of incest: the father’s forbidden desire for his daughter becomes the master script for all cinema. A section in “Every Man for Himself,” aptly titled “Fear,” shows the “Godard” character speaking of his sexual desire for his eleven-year-old daughter. In “First Name: Carmen,” a contemporary version of the opera (with Bizet’s music replaced by Beethoven quartets performed onscreen), Carmen plays on the incestuous longings of her Uncle Jean to lure him into making a movie that will serve as cover for her band of robbers. And in “Hail Mary” (1985), a modernization of the story of the Virgin Birth, Godard introduces the theme once more. Remarkably, the film that Godard originally proposed to its lead actress, Myriem Roussel, was a non-Biblical drama on the subject of father-daughter incest, in which the male lead would be played by Godard. It was only after Roussel’s refusal that, as Godard later said, “it occurred to me: God the Father and his daughter.”

But as Godard was taking on the grand themes of Western civilization—European painting, opera, classical music, psychoanalysis, Christianity—the world, particularly the American movie world, was heading in a different direction. In the United States, the appeal of foreign films has always depended on their blend of intelligence and sex, but Godard’s movies were unusually demanding intellectually, and the sex wasn’t fun. At the same time, after the financial success of Spielberg’s “Jaws” and George Lucas’s “Star Wars,” Hollywood was gearing its movies to the adolescent raised on TV, and the burgeoning American independent cinema likewise offered a more familiar set of references. Even the most striking of the independent films, like Jim Jarmusch’s “Stranger Than Paradise,” didn’t demand a knowledge of Delacroix or Beethoven to be appreciated.

Paradoxically, Godard’s reliance on recovered fragments of Western culture lent his films a new emotional depth. Yet his work of the mid-nineteen-eighties was released commercially in the United States with little fanfare—until 1985, when “Hail Mary” generated a controversy too heated to be ignored. Although the film’s outward elements seem jokey (Joseph drives a taxi, Mary helps out in her father’s gas station and plays on a girls’ basketball team), the tone and import of the film are sublime and respectful, and have even suggested to some a powerful, non-dogmatic argument for Christian faith. Many believers, however, were disturbed by other aspects of the film: Mary is shown not only nude but in erotic agony, as if she were in the throes of sexual possession, presumably by the Holy Spirit. The film met with protests, sometimes violent, in cities throughout Europe and the United States. When Pope John Paul II criticized it, Godard responded with a barbed apology, requesting its withdrawal from the Italian market: “It’s the house of the church, and if the Pope didn’t want a bad boy running around in his house the least I could do is respect his wishes. This Pope has a special relationship to Mary; he considers her a daughter almost.”

At the 1985 Cannes Film Festival, flush with his renewed celebrity and notoriety, Godard approached Menahem Golan, of Cannon Films, and asked him to produce a film of “King Lear.” Golan agreed, and wrote out a contract on a napkin from the bar where they were meeting, adding one clause: the script would be written by Norman Mailer. Godard was delighted with the plan: “It was King Lear and his daughter Cordelia that I had in mind, a little like God and Mary in the other film.” At first, Mailer balked, assuming that Godard was “hell on writers.” He was persuaded, he told me, only by Golan’s offer to let him direct his own film, “Tough Guys Don’t Dance,” if he agreed. Godard’s first move was to sign Orson Welles as an actor, or “guide”; but after Welles died, later that year, Godard came up with another idea: Mailer himself would play King Lear, and his daughter Kate, an actress, would play Cordelia. This, too, Mailer accepted, with misgivings.

“I finally decided that the only way to do a modern ‘King Lear’—because that was what Menahem Golan wanted—was to make him a Mafia godfather,” Mailer said. “I couldn’t conceive of anyone else in my range of understanding who would disown a daughter for refusing to compliment him. So I turned it into a script I called ‘Don Learo’ ”—pronounced “lay-AH-ro”—“which to my knowledge Godard never looked at.” Mailer shouldn’t have been surprised, inasmuch as Godard hadn’t read Shakespeare’s play, either. Instead, Godard admitted, he watched all the available filmed versions of it: “I had a vague idea that there was this girl who says, ‘Nothing,’ and that was enough.”

Although Godard had intended to make the film near Mailer’s house in Provincetown, he suddenly summoned Norman and Kate Mailer to Switzerland. “When we got there, to the hotel, he wanted to start shooting right away, and so he started giving me lines, and I was hardly playing King Lear. He said, ‘You will be Norman Mailer in this.’ And then he gave me some lines, and they were really, by any comfortable measure, dreadful. They would be lines like, I’d pick up the phone and I’d say, ‘Kate, Kate, you must come down immediately, I have just finished the script, it is superb’—stuff like that. He was shooting, and we were getting some dreadful stuff. . . . I said to him, ‘Look, I really can’t say these lines. If you give me another name than Norman Mailer, I’ll say anything you write for me, but if I’m going to be speaking in my own name, then I’ve got to write the lines, or at least I’ve got to be consulted on the lines.’ So he was very annoyed and he said, ‘That’s the end of shooting for the day.’ ”

Godard conceded that the difficulties in their relationship stemmed in part from his way of working (“I don’t know very well what I want to do, so he couldn’t really have a discussion about it. He had nothing to do but obey, to have confidence in me”), but he also believes that Mailer was hostile to his vision of the film, which was supposed to be like “reportage” of Mailer’s relationship with his daughter. “When he saw that he was going to have to talk about himself and his family, it was all over, in a quarter hour,” Godard told me. “And that’s the little piece that stayed in the film, but he left the next day” (a mutual decision, according to Mailer). To Danièle Heymann, a journalist from Le Monde who visited the set, Godard added one fillip: “He left, being unable, he said, ‘to see himself represented in a situation of incest.’ ” When I mentioned this to Mailer, he asked me, “Is it a reasonable demand to ask someone to, in their own name, play that they have an incestuous relationship to their daughter?”

After Mailer quit, Godard asked Rod Steiger, Lee Marvin, and Richard Nixon to play the part; all three turned him down. Finally, he replaced Mailer with Burgess Meredith, and asked Molly Ringwald to come to Switzerland and play Cordelia. Ringwald told me that she was fascinated by Godard’s spontaneous working methods, but she freely admitted that she didn’t always know what he was up to. She also called attention to an aspect of his films that, she says, is often overlooked—their humor. Ringwald said Godard was “a great joker” on the set, particularly with Meredith: he “short-sheeted Burgess Meredith’s bed,” and “put fake blood on his bed, too.” Heymann had watched Godard set up a shot of Meredith’s bloodstained bed, however, and had asked Godard’s assistant about it; the assistant explained it as evidence of Cordelia’s lost virginity. The scene as filmed includes neither Cordelia nor Lear, and, indeed, Ringwald was unaware of the sexual subtext during the shoot, but in the finished film the incestuous implications are clear.

True to Godard’s later style, the film’s real story is precisely how to tell the story, or whether it is in fact possible to do so. The film is constructed around a frisky, quizzical character called William Shakespeare, Jr., the Fifth (acted by the theatre director Peter Sellars), who has been hired by the Queen of England to recover the works of his ancestor, which have been lost, along with the rest of culture, in the technological holocaust of Chernobyl. In the course of his tragicomic quest, Shakespeare, Jr., meets a reclusive professor—Godard himself, adorned with jingling dreadlocks made of video cables—who has reinvented the movie theatre in an attempt to rediscover “the image.” The professor’s ultimate creation is springtime, which he achieves, on Easter Sunday, by reattaching the petals of dead flowers through the miracle of reverse photography—an effort that costs him his life but makes possible the “first image.” This image turns out to be a cinematic crystallization of “King Lear” ’s most tragic moment: the tableau vivant in which Cordelia lies dead and her father must acknowledge the reality of her death.

Godard’s “rediscovery” of Shakespeare is a grand statement about the power of moviemaking—its ability to appropriate and restore all other art forms. Yet “King Lear” makes an even more extravagant claim on behalf of Godard himself: that the cinema has been lost, and that its reinvention, and therefore the rediscovery of all art, is Godard’s personal mission. His artistry, he suggests, can even revive nature, making flowers bloom again in spring. The cost may be great, but then the ultimate creator whose work Godard would subsume under his own is God.

Godard has said that he doesn’t have a “pile of scripts in a drawer waiting to be filmed.” Most of his films are based on stories that come to him on the spur of the moment, once the money is in hand. But one project that weighed on him for decades was a visual history of the cinema, which he started shooting, on video, shortly after he finished “King Lear.”

This eight-part series, which the director finally completed in 1998, is called “Histoire(s) du Cinéma.” It is not a comprehensive narrative history but a willfully subjective meditation on themes from the cinema that connect speculations about history and culture with an intimate yet cosmic vision of film. In one episode, Godard declares that the cinema “was the only way to make, to tell, to realize: me, that I have an histoire in and of myself.” The hundreds of video clips that he juxtaposes and superimposes are related by associations that feel as private as those from the mental screen on which the films of his life have been projected.

The first installments of “Histoire(s) du Cinéma” were completed in 1988, and their effect was immediately evident: Godard stopped appearing in his features, and the films—“For Ever Mozart,” “Hélas pour Moi,” and “New Wave”—displayed a newfound grandeur and classical balance. It is as if the “Histoire(s)” had become the outlet for the irrepressible profusion of thought and the need to give himself voice that marked Godard’s earlier work.

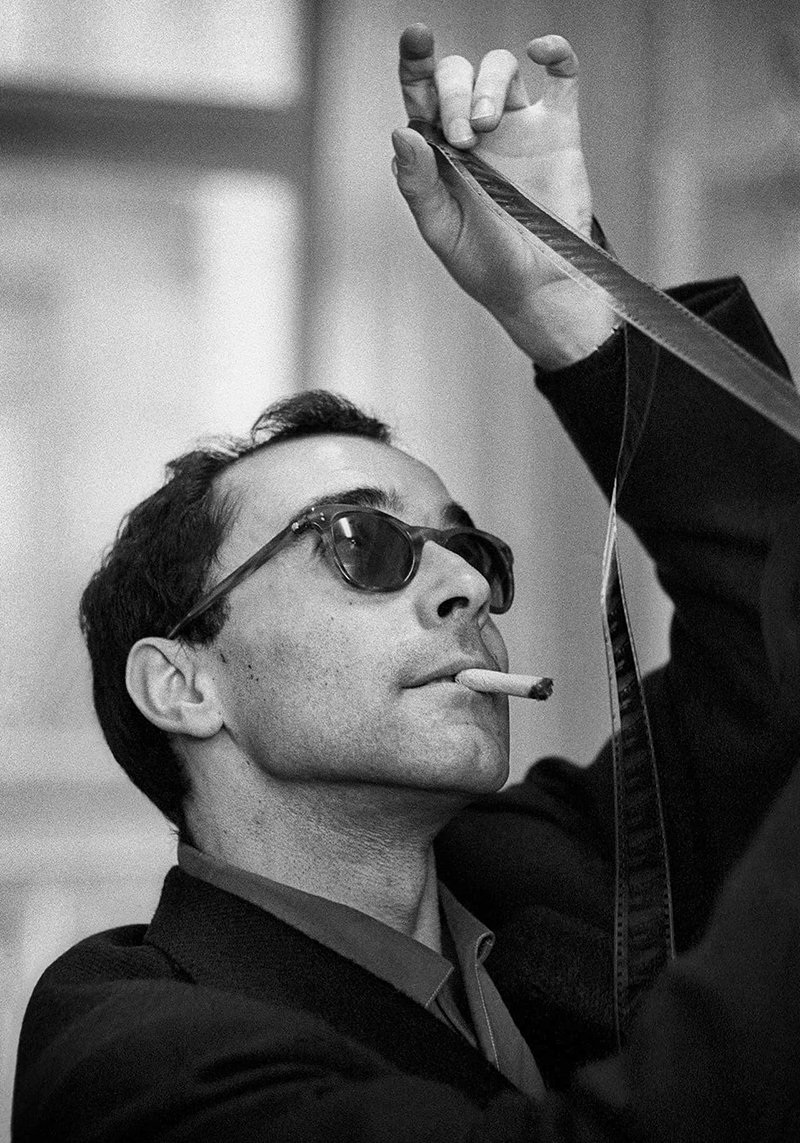

Godard photographed by William Klein, in 1960.Photograph from Contact Press

As the title suggests, “New Wave” is the story of the French New Wave, albeit treated allegorically. Alain Delon plays identical twins who are never seen together: the film begins with the weak one (who represents earlier directors) being rescued and dominated by a powerful woman (the cinema), who finally does away with him; it ends with the strong one (the New Wave), who finds the woman weakened and puts her troubled affairs in order. The characters speak in poetic phrases borrowed from literature; Godard had his assistant search through dozens of literary works in search of potentially useful phrases. “There isn’t a word of mine in it, not a word,” Godard told me. “Maybe one word of mine, ‘Hello, how’s it going’—I think that’s all.”

He went to the shelf to get me a copy of the CD release of the soundtrack, and asked me if I had seen the new set of CDs, with lavishly illustrated libretti, of “Histoire(s) du Cinéma.” I asked him about this diversification. “Everything, everything is cinema,” he replied. “Everything is cinema.”

As Godard’s films went off in new directions in the early nineties, Godard himself was looking for ways to expand his contacts with the new generation. In 1990, he and Miéville signed a five-year deal to move their studio to the premises of La Fémis, the prestigious film school in Paris, but the arrangement fell through. A few years later, he approached the government-funded acting conservatory of the Théâtre National de Strasbourg about making a film with its students, “The Training of the Actor in France,” but both the administration and the students were unreceptive to Godard’s ideas. At the same time, his name was floated for a chair in the Collège de France, a French academy similar to the Institute for Advanced Study, but there he also met with opposition. Thrown back on his own resources, Godard was bitter but not surprised. In his self-portrait film, “JLG/JLG” (1994), he contended that art is the exception while culture is the rule. And, he added, “it is part of the rule to want the death of the exception.”

Godard has not denied that there was also a financial motive for seeking these institutional connections. He has said that his goal is “to be a filmmaker and state functionary, as in Russia. . . . My dream is to work by the month and by the year.” He also told me that he has sold the rights to “three-quarters” of his films to the major French film-production and distribution company Gaumont. “I’m arriving at the end of my life: I haven’t made any money, I have nothing put aside,” he recently told another interviewer. “No pension, no Social Security. If I have an accident. . .”

In fact, Godard has been making videos on commission since the seventies: his clients have included Britain’s Channel 4, France Telecom, the French appliance store Darty, and UNICEF. He told me that one such video, “Les Enfants Jouent à la Russie,” from 1993, was commissioned privately by an American producer, who has never shown it. Godard himself has no copy of it. When I mentioned that I had seen it, he said that it must have been “a bootleg.” Most recently, he completed a thirteen-minute piece for the opening ceremony of the 2000 Cannes Film Festival, “The Origin of the 21st Century,” a caustic postscript to “Histoire(s) du Cinéma,” in which he offers a retrospective view of the twentieth century which juxtaposes clips of feature films with documentary images of the horrors the films failed to respond to. Received with bewilderment at Cannes, it was shown twice last month in a program of short videos at the New York Film Festival. The Times review of the program failed to mention it. Both showings sold out.

In 1998, Godard and Miéville made a fifty-minute video, “The Old Place,” that was commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art. “We were paid five hundred thousand dollars for it,” Godard told me. “Well, I thought, five hundred thousand dollars for a film that we’ll finish in two weeks, not bad. But it took us a year to figure out what to do, to find the images, to choose the texts, et cetera. Then, after taxes, the cost of production—what’s left?” “The Old Place” has not yet been shown publicly, and Godard wonders why not. He assumes that “they” don’t like it: “Maybe they thought I was going to spend a lot of time in the museum, film their collection.”

In the film, Godard and Miéville condemn Andy Warhol as a mercenary, reject abstract art as the work of artists who can no longer face history, and divide art into its visual component (starting with fields of flowers) and its political aspect (exemplified by documentary images of suffering). It is a provocative and disturbing work, and someone who views it in one of MOMA’s belowground theatres may be moved to take a long, contemplative detour through the streets and the Park before daring to go upstairs to indulge in the museum’s collection. I spoke with Mary Lea Bandy, MOMA’s curator of film and video, who greatly admires the piece, and is proud to have arranged the commission. She considers Godard “as complex as Picasso or Dante,” and says that he is “arguably the greatest living artist.” She told me that “The Old Place” is to be shown at MOMA in February. She hopes to persuade Godard to come to New York for the occasion, but she understands his aversion to such events: “He’s like a monk who has gone to the monastery to brood. There’s a great deal of sorrow in what he’s brooding about. The political idealism of socialism has disappointed him, yet he’s very angry about the way that capitalism is managing things.”

I asked Godard about the evolution of his politics. “We were for Mao, but when we saw the films he was making, they were bad. So we understood that there was necessarily something wrong with what he was saying.” For Godard, the “reference for measuring, even for politics,” is the cinema. He brought up the French farmer José Bové, who has recently become notorious in France for demolishing a McDonald’s to protest globalization. “At bottom, I think he’s right, but what bothers me with him is that if you show him a film of Antonioni he won’t like it. So I’m suspicious. That’s how we’ve stayed, completely, since the New Wave, we movie people. We’re pretty sectarian, even ‘racist’—in quotation marks, so to speak—in relation to cinema. If nobody makes good films, if nobody can make good films, then it will disappear. But as long as I’m alive it will last—let’s say for twenty years.”

The coming months will be active ones for Godard. Anne-Marie Miéville’s latest film, “After the Reconciliation,” which co-stars Godard, had its first press screening last week in Paris; two days later, the filmmakers presented it to high-school students of cinema in Sarlat, in southwestern France. The film will open in Paris and elsewhere in France on December 27th. “The Old Place” will première at the Cinémathèque Française in January, and “In Praise of Love” is scheduled for release in February or March. Meanwhile, Godard has also edited the five hours of “Histoire(s) du Cinéma” into a ninety-minute version, “Moments Choisis,” which will be released in French theatres at the beginning of next year.

Nonetheless, this flurry of attention cannot conceal the fact that, with the completion of “Histoire(s) du Cinéma,” which in a way is also the histoire de Godard and the histoire du monde, Godard has reached a high, remote plateau, from which he appears to be looking for a hand down. He told me that leaving Rolle might be the answer: “We’ve been saying that it’s our studio here, our studio of exteriors, between Geneva and Lausanne. The area is just about the size of Los Angeles, but here there are forests, the lake, snow, mountains, and wind. . . .But now we’ve had our fill, so to speak, of all these places, so we have to find something else.”

After our interview, Godard tossed a black blazer over his T-shirt and invited me to have dinner with him at the restaurant of the hotel where I was staying. We walked downhill from his office to the hotel’s broad, pebble-strewn terrace, where there were some fifteen widely spaced tables. Neither patrons nor staff acknowledged the filmmaker in any exceptional way. As we ordered, Godard decried the state of the world, using the cinema as a touchstone: “Before, if you had a little money, you could make a film like Cassavetes. If you had a lot, you could make a film like Kazan. Now they don’t know how to do either one. They don’t know how because they’re not interested. Producers aren’t interested in doing cinema, actors aren’t interested in doing cinema, doctors aren’t interested in doing medicine, psychiatrists—there are still a few who are interested, but that’s starting to disappear, too.”

Godard ordered a slice of fruit tart for dessert, and when I ordered an espresso he suggested I try a ristrette instead, a highly concentrated semi-demitasse, which is a local favorite. He ate the glazed baked fruit off the top of his pastry and grew wistful. “I’ve been sad for so long that now I’m making an effort to be more contented,” he said. “Otherwise, one would have reason to cry all the time.” When we parted for the evening, he told me to come by his office the next morning.

At the appointed time, I found curtains drawn over the wall-size window and the glass door, to which a note inscribed “Mr. Brody” was taped. Godard had written that he could not continue the interview because “it was not a real discussion” and was “flou”—out of focus, vague—but he wished me a better “game” with people I’d be seeing in Paris. I had been warned that this sort of thing might happen; one acquaintance in Paris had told me, “Il est déstabilisateur né”—“He is a born destabilizer.”

Returning to the hotel terrace for a coffee, I asked the waitress who had served us the night before whether she had recognized my dinner companion. The woman replied, in a rapid, animated voice, “Oh yes, I know him well. He comes here pretty often, but we leave him alone. People ask us to get his autograph for them, but we don’t do it. He doesn’t like that. He came here to be in peace, and we leave him in peace. He’s a very good customer—he’s always contented, he never complains. If all our customers were like that, this would be a dream job.”

I had expected that Godard would avoid the hotel that evening, but perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised to see him in the dining room with Anne-Marie Miéville when I went in for dinner. I approached him and said “Bonsoir.” He hardly looked at me, and, with a forced smile, emitted a chilling “Bonsoir.” Miéville scrutinized me, and then glanced back at him. I thanked Godard for his time, he thanked me and wished me “Bon voyage,” and I returned to my table.

From across the noisy room I could hear only Miéville’s high, flutelike voice, descanting loudly and emphatically: “Brigitte Bardot. . . Cannes. . . to drop off his screenplay. . . he’s waiting. . .budget. . . doing the color timing before the editing. . . . ” Occasionally, she would pause, and he would murmur haltingly before she resumed.

The scene reminded me of two films. The first is by Miéville, “We Are All Still Here” (1997), a meditation on a woman’s search for “the good man” (adapted from Plato’s “Gorgias”), who turns out to be an introverted old actor, played by Godard. The woman prods him into better manners and more patience with worldly foibles, and he endures her tender harangues. The second is “Two Weeks in Another Town,” by Vincente Minnelli, which Godard calls one of “the only two good films on the cinema,” in which a tyrannical director (played by Edward G. Robinson) clashes with his strong-willed wife, who is nonetheless his only consolation when a producer intrudes on his art. Afterward, when I saw the waitress in the corridor, she said, “You know, he’s very unsociable. Very shy and very unsociable. He hardly ever talks. She—his wife—she talks, but not him.”

Walking along the lakefront in Rolle in the twilight of the summer evening, I recognized many of the elements of Godard’s later films: the lapping of water on rocks; the constant and startlingly various voices of birds; the rhapsodic blue of the sky; the vapor trail of a small, potent airplane; the rustle of leaves in the wind; the short, hollow peal of an ancient church bell; and, most of all, the sense of a last refuge. I also noted the lack of a good movie theatre. I thought again of the filmmaker’s plans to leave town, and wondered where he could go.

A move wouldn’t be easy, but very little about Godard’s professional life feels easy. Godard has put himself in a singularly unenviable position: he has taken the entirety of the cinema upon himself, has identified its survival with his own, has assumed the burden of its fictional forms like the mark of sin. If the new generation of French directors—and, for that matter, American independent filmmakers—feel it unnecessary to confront the history of cinema in their work, it is because Godard has done it for them; they have been freed of the burden of the classical cinema by his sacrifice. At the same time, Godard’s highly particularized obsession with the past and future of filmmaking has left him with virtually no share in its present. It is as if he had exchanged his place on earth for his place in history.

As I tried to imagine where Godard could go next, Hawthorne’s story of Wakefield came to mind: a man intending to leave home for a week stays away for twenty years and then “entered the door one evening, quietly, as from a day’s absence.” Although Hawthorne gives the tale an equivocally happy ending, he follows it with a frank declaration of its darker purpose: “Amid the seeming confusion of our mysterious world, individuals are so nicely adjusted to a system, and systems to one another, and to a whole, that, by stepping aside for a moment, a man exposes himself to a fearful risk of losing his place forever. Like Wakefield, he may become, as it were, the Outcast of the Universe.”